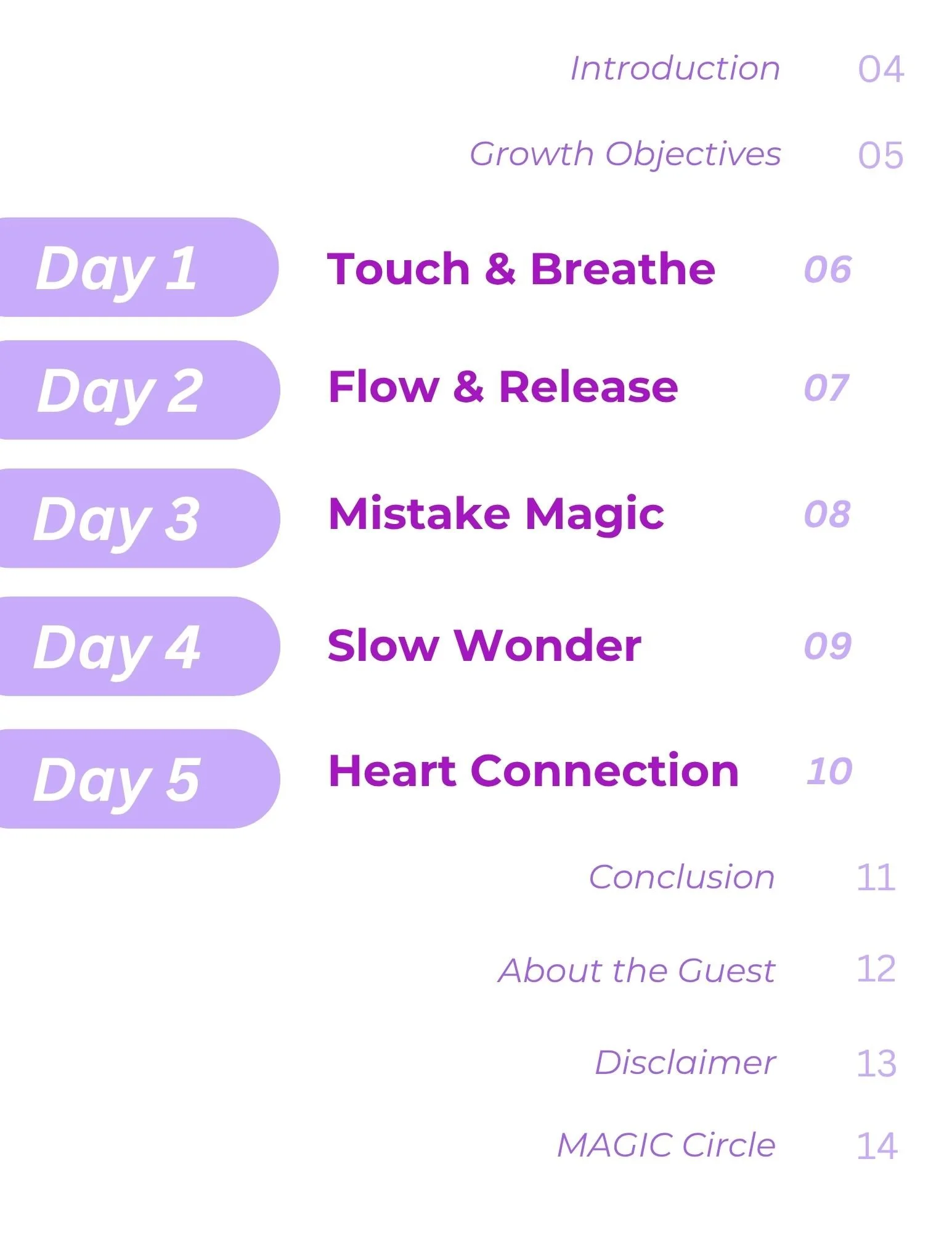

Let MAGIC In: How Process-Based Creation Transforms Leaders | Judy Tuwaletstiwa

When artist Judy Tuwaletstiwa introduces herself to an imaginary alien visitor, she doesn't speak—she brings her hands to her heart. This simple gesture embodies decades of wisdom about how physical creation can transform not just artists, but leaders, decision-makers, and anyone seeking deeper connection in an increasingly uncertain yet exciting world.

The Awakening

At 29, Judy was an English teacher raising four children when a Van Gogh exhibition at San Francisco's de Young Museum changed her life: "When I stood before one of his final paintings, Wheat Field with Crows, I started crying. I couldn't stop. Something opened in me that had been closed since I was 11 years old when an art teacher told me I was no good at art."

That devastating childhood moment had silenced her artist voice for nearly two decades. But Van Gogh's paintings did exactly what he had hoped—they opened "the wellspring of a person's heart." Judy returned home, grabbed a piece of mat board, and made her first drawing in almost 20 years, writing four sentences on the back that would guide her next 50 years of creation.

"I didn't really have a choice," she reflects. Art ambushed me."

-

MAGICademy Podcast (00:00)

Clay is this geologic time. It's taken millions of years for the clay to form. And we're lucky enough to be able to hold it in our hands. Very different relationship to time and to process. There are no mistakes in art. What we think of as a mistake is simply a doorway to another way of seeing. Just observing. Pretty soon you know what somebody needs to be doing. Life is a very complex holding structure. And south is the pilgrimage.

Jiani (00:28)

Welcome to MAGICademy podcast. Today we have a special guest, Judy. She is an artist, a mother, an explorer, a grandmother, an explorer for the arts and how art can potentially unite people and connect people on a much deeper, way. And such a pleasure to have you, Judy.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (00:54)

Thank you, Jiani It's lovely to be

you for inviting me.

Jiani (00:57)

I noticed I said explorer

twice and I think it matches you a lot because your life is an exploration and we will talk more on that. I think the first question is a spaceship just landed in front of you out walks a friendly alien

If you were to use one word or one movement to introduce yourself, what would that be?

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (01:23)

I bring my hands to my heart.

Jiani (01:25)

Why art?

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (01:26)

Why art? I didn't really have a choice.

I've often said art ambushed me. I had become a teacher of English secondary school, teacher of English literature, or of English. I had no idea I was a visual artist too. And I'm really glad because when I went to university, I studied English literature. And I had a mother who taught me to write.

And then a father who was an amazing storyteller, Southern. Southerners can have a special way with words. And when I went to university, I thought I'd become a teacher and I studied English literature, both undergrad and grad. And then when I was around 29 and I had three of my four children.

I went to an exhibit of Van Gogh's work at the D. Young in San Francisco.

left the children with the babysitter and my first husband Michael and I drove up to the city from Menlo Park where we lived, about an hour from San Francisco. And when I finished walking through the exhibit, I started crying and I couldn't stop crying.

Something had opened in me. So there's that gesture again. Something had opened in me that had been closed since I was 11 years old when a teacher told me I was no good at art. After I'd stayed up all night doing a painting of the rain on the streets in Los Angeles where I grew up. And you know, these incidents happen in our lives.

And it was really devastating when she said that, but I look back at it now from my 80s and I realize if I had touched into this place where my art comes from, where Van Gogh's paintings allowed me to go and open again, it would not have been good for me as a child. I was raised in a very chaotic household.

and to be that deeply in touch with the unconscious would not have been good. I also learned how not to teach when that happened. She was a perfect example of how never to teach. So it served its purpose. I shut down the part of me that could get lost in the art.

and I became a school leader, worked in my community, we're still very close friends, all of us who worked together in high school. But 60 something years later, we're still very close. So it allowed me to do something else that I might not have done if I had followed the art. But when I was 29, I was a bit overwhelmed with raising children and...

going to the Van Gogh exhibit, opened my heart. And later I read something Van Gogh had written to his brother, Theodore. And he said that what he wished is that his art would open the heart, how do you say, the wellspring of a person's heart. And that's what he did.

Someone who could never imagine standing in San Francisco at a huge retrospective of his. It opened that wellspring. And I came back home and I grabbed a piece of mat board that was lying around and I did my first drawing in almost 20 years.

And on the back of it I wrote four sentences that have led me.

for the past over 50 years now.

And that's how I started doing art again. So it was

Technique has never been important to me. It has always been the concepts and the technique always grows out of those concepts.

It's magical how these, you you come into the studio with an idea and then the materials take over.

My friend Lee Perrin, who's a wonderful poet who lives in California, once said, experience is so much deeper than our visions.

And after over 50 years of doing art, I can say that I totally, totally believe that each day is you use the word explorer twice each day is an exploration.

A wonderful man who is head of the Modern Elder Academy up the road here in Galistale. Yeah, Chip, wonderful Chip. Chip was talking the other day, he had a gathering for this, for us in Galistale. Pico Eyre had given a workshop and they spoke together a bit. And Pico asked all of us who were sitting there,

Jiani (06:03)

⁓ chip.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (06:21)

about pilgrimages, what pilgrimage had we taken that was meaningful to us, and I suddenly realized that life to me is a pilgrimage. There might be chapters within that, but that life itself is the pilgrimage.

Jiani (06:35)

Yes.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (06:36)

And the art is such a basic part of that for me. And the art in everybody. Some of us have to be artists every minute. That's what I have to do. I mean, I'm down in my studio every single day. But everybody can do art. Everybody needs to express themselves at that level.

Jiani (06:48)

Creating

sometimes when we're thinking about arts, it's usually for most people, it lives in the museums. It's like far away from our daily life, connections and leaderships and self -awareness.

personal development and all that feels like there's like two separate things and how how does art actually help us become more self -aware become deeper connectors and maybe reawaken our creativity that's among everyone not only artists how

How does, how can art help us to reach that enlightenment per se?

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (07:39)

I think you were answering it with the movements of your hands. You were saying, how can art help us? And you made this connection between your hands like a global connection. And I think, and again, you did it here, close to your heart.

Jiani (07:42)

Yeah.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (07:56)

And I think that's what art lets us do. And I'm talking about actual materials, not Photoshop, not being on the computer with our fingertips. the philosopher Immanuel Kant said that these are the visible part of our brain. These hands. And if we only use them on the computer.

That's one use and it's a helpful one. But it's picking up clay and working with clay.

I wish everybody who's listening would find some clay or mud. I'm not talking about plasticine. I'm talking about something from the earth itself. And just put it in the air and just like in even sand. And what's so interesting, again, you're using both your hands equally. The thing that's so amazing about clay when I do exercises with people with clay is your hands are equal in dexterity.

You don't have a second thought about doing the finest work with your less dominant hand. There is no dominant hand. And I think that happens with clay more so than almost any material.

And Clay is such a, you know, it's geologic time. It's taken millions of years for the clay to form. And we're lucky enough to be able to hold it in our hands. And I have told teachers years ago when we had wonderful programs in Healdsburg, California, great arts programs, we brought many artists into the schools.

that if they had a small plastic bag of clay and they started with that every single morning with the children and did a very simple exercise that they would have a different child on their hands for the rest of the day. Just took 20 minutes in the morning not rushing ahead to anything.

And even in corporate America, if people did that, they would have a very different relationship to time and to process.

Jiani (10:05)

Tell us more about the process. In our initial conversation, you were talking about process -based art making. And what role does this process play in creating?

accessible art for everyone.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (10:23)

First, you have to accept that there are no mistakes in art, not if you approach it this way. That every what we think of as a mistake is simply a doorway to another way of seeing or thinking. And that's been my experience now for all these decades. As I've taught myself.

and as the materials have taught me.

So when you're deep in process, you allow for concepts to come up from the unconscious. If you're not trying to get to a goal, like one of the ways that I taught myself, but this is back in 1985, was I didn't know how to stretch canvas at that point. I had worked with other medium, including weaving.

which is the base of, conceptually the base of everything I do. So I think life is a woven structure, very complex woven structure. But.

I had John Anasly in Healdsburg, who is a master canvas maker, stretch a six by four foot canvas for me, knowing that none of the paintings on that canvas would ever exist except as memory, except as photographs. And a photograph is not the painting. A painting has a presence that the photograph of a painting cannot have. And

I decided I would load my camera with a roll of 36 frames, because back then we didn't have digital. And I would paint. And then when the painting felt like it should be photographed, I would photograph it. And then I would continue painting.

And I did a hundred different paintings on this canvas, knowing that there would be one final color of light that would cover all of them. So that none of them would exist except as memories. I was trying to teach myself. I thought I was. I remember when I had the idea.

I was sharing the idea with the man who is now my husband, Philip, on the phone, because he said, how do I learn to paint? I said, do what your people did a long time ago. Philip's father was Hopi Indian. And they would paint these enormous Kiva murals in their religious Kiva, do their ceremonies, and then whitewash them eventually.

So like on one wall of an ancient cave, there were a hundred layers of murals.

So any, and whitewash and the whole wall built up, but what you knew is that your ancestors' hands were on that wall going back generations. It was such an amazing concept. And I said to him, why don't you set up a camera, go to the art store and buy a little canvas, because he lived in a little apartment.

Jiani (12:55)

They keep whitewash it.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (13:19)

Buy a little canvas, get white, black, red, yellow, blue, acrylic. Do not look at color charts. Mix your colors, get to know them. Paint. When the painting feels complete, photograph it, whitewash it, then do another one on top and do it for 36 photographs.

then look at the photographs and you'll understand something about your own process. So of course, Philip didn't do it and I got off the phone and I thought that is one great idea. But I did not whitewash in between. I just let the story create the story, create the story. And Jiani, I love some of the paintings so much. It was so hard to let go of them.

Others I just hated. They were chaotic. They were what I would call ugly. They didn't feel connective. But guess what? I had made them. So I would always, it was an interesting experience because I would usually, if I disliked one of the paintings, I would force myself to sit with it for, until I could appreciate it.

And it would usually take about three days. When I loved a painting, it would take about three days until I could let go of it. So what I learned, you ask, what is process? That to me is the essence of process, what happened with these paintings. And what I learned is how to let go in art.

Jiani (14:48)

whether you like it or you don't like it when it doesn't matter. You have to let go.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (14:48)

It was

It doesn't matter.

being able to let go and let something happen that you cannot even begin to predict. It was a powerful, I did a white painting in 1985.

a black painting in 1986 and in 1987 a red painting. Each one has a hundred photographs approximately. The first one, the white painting, I did it over six months. The black painting over two months. And the final red painting over two weeks.

and they still all ended up with about the same number of photographs. And I have learned, I did them for myself, not to show publicly. I did show the red painting, worked with a wonderful printer in Santa Fe, Steve Zeifman, and I showed...

about 75 of the photographs at a show at the Center for Contemporary Art, part of the show. It's the first time, I did it in 1987 and showed it for the first time in 2019. That's another important thing about process, time.

We're always in such a rush. How do we let go and let some of my series, there was one I did in 1993 and in 2017 I realized I hadn't finished it. And it gave birth to a complete series that was a response to it and then it was done.

Jiani (16:17)

We are.

feels like time is like an essential ingredient because when we're talking about process because the process is linear because of time there is process without time and everything exists at the same time and different dimensions. How do you, how do leaders

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (16:43)

Yes.

Jiani (16:59)

balance or balance is a tough word because it's hard to just balance two things feels like they're separate well be a different word

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (17:09)

I think balance is a good one. Yeah, you think of the scale, the balance scale, and how this, when things are balanced, there's this sense of centering, of being centered.

Jiani (17:10)

It's a good

Hmm... Harmony.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (17:24)

Harmony is part of that. That's the feeling when you look at something that's truly balanced. There's a sense of harmony. That's a wonderful word to use.

Jiani (17:34)

So how does leaders, inspired by the process of making

of practicing letting go whether you like it or not how does how can leaders future leaders current leaders integrate this philosophy and being able to balance and harmonize getting control and letting go

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (17:55)

That's a big question. That's a big question.

Jiani (17:57)

Probably three days if they need.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (18:00)

Yes, yes, we could do a whole workshop on that. I think.

I remember there was a workshop that I did with hardware designers.

And that evening, two of the men picked up, they were so used to working on their computers designing hardware for computers. But they picked up a piece of wood and shaped it and started working with it. I think it all comes back again and again to connecting with our hands.

I mean, it's as simple as someone struggling with an idea, pick up some finger paint and sit and finger paint. It's not like you're making something to show to people, but it helps lead us. I've seen so many times when people are stumped by something and I'll give them a piece of clay.

and ask them not to make anything to let one thing become a sort of like it's a takeoff on what I did with the photographs, except this is writing down what the clay becomes as it keeps changing and how people find their way through the problem by letting go. know, control only goes so far. I think it's the letting go allows.

other threads to help weave the answers.

And that takes time.

And time has so many forms. I mean, if we think of time as cyclical.

Jiani (19:17)

follow up question.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (19:22)

if we think of it as, we can think of it as just one long thread. We can think of it all balled up, filled with knots. I mean, there's so many ways to think of it. And if we just let our thinking flow around some of that, I think it gives us the presence to see that we are not in control.

and that things can come together in a different kind of way.

We might not always be happy about it.

but it's the way life really does work. That's been my experience.

And, you know, I've become very skilled at doing my art and letting the stories arise and surprise me. But the longer I do my art, the more mysterious the whole process becomes.

Jiani (20:06)

Hmm.

also taps into the abundance mindset because sometimes the reason behind

control is because we need to reach a certain outcome by a certain time.

Otherwise we will be missing the opportunities and which sometimes can be true. Maybe.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (20:30)

Yes.

Jiani (20:37)

Usually in a very competitive environment, survival is number one for big organizations or even startups.

How can this openness to possibilities, mindset of even if we make mistakes this time, surprise will come, abundance will come, alternatives will come.

how yeah how maybe there's no answer but i feel like compelled to ask this question

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (21:03)

I don't think there's,

I think one has to experience it. I know that the more that I slow down, the more threads weave themselves together. The more I'm able to see that. I think the problem with rushing and always trying to get the answer, trying to control something is you don't see, it's like,

an escalator is going down and you're running up it.

and it's exhausting.

And the slower...

I go, I'm one of those energizer bunnies. I mean, I was one of those people who could work 16 hours a day in my studio. But what I've learned, because a lot of my work is repetitious in the sense of very small pieces that come together to create a larger piece. And it changes depending on the materials that I'm working on. But there is always this

having to pay attention to detail. The art has taught me how to move slowly in the world.

It doesn't mean that I think slowly. I mean, I connect ideas. I'm one of those people who's a leap thinker where an idea would connect like this. And I've had, over the years, the art has taught me how to help people see the steps in between.

Otherwise, it's too confusing to communicate those ideas.

it really is, jiani you say magic. Doing art every day, whether it's waking up in the morning and somebody just making a mark on a piece of paper, that's all. And doing it every morning for a month and then looking at those marks and wondering what they tell them.

You know, not hanging it in a gallery, not doing anything like that, being, yes, but just being with that action.

Jiani (22:56)

Even though it can.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (23:01)

I said, I've got to do this today. I've got to do this. I've got to do this. I've got to this. I make a list each day of everything that I need to do. There's a lot going on right now in my life. a number of books that I'm working on. And I had a show that opened in Santa Fe with a wonderful artist from London, a Nepalese man. And our work really speaks to each other. It's a joy.

to hear the conversations between our work. Govinda, wonderful, wonderful artist. I'm giving a workshop.

to people who are asking some of the same questions you're asking. And I'll work with them. And the way that I work with, it's like just observing. And pretty soon you know what somebody needs to be doing. You don't know the answer for them. But by observing, I can tell, hmm, I wonder if watercolors.

to help right now. Or maybe this person should sit in the creek with the watercolors and just watch them flow for a

and then do something on paper.

or maybe this or maybe that. And everybody's different, but these materials are so, I mean, I wish every leader would have crayons, a big box, 48, a box of crayons in their desk drawer, including the president of the United States, including any president. One of those kids watercolor sets.

Nothing fancy. A plastic bag with some clay in it.

When I was in Ukraine doing the mural in Lviv, I was talking to Tomas, who was the attache with the Lithuanian embassy who had arranged for us to go to Ukraine. Seven of us artists from four different countries. We had a five story building to paint, each one of us having a mural.

Yeah, there was scaffolding all the way up. Mine was down low. They definitely didn't want an 83 -year -old woman climbing up the scaffolding. But Tomas, the attache, was speaking about all the art therapy programs that they have in Ukraine right now. A country with probably more art therapy programs than any country, both for the soldiers and for the children.

Art really can connect what is divided. And that's what you had, we were talking earlier about the wall between Gaza and Israel. Why are we killing each other?

You know, why are we dropping bombs and shooting and murdering?

The wall that I had imagined, because I worked with glass at this point, I had pictured the sand that blows back and forth, back and forth between Israel and Gaza. It doesn't know any boundary or border.

Jiani (26:05)

No.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (26:06)

And I thought we need to get Palestinian and Israeli glass artists. mean, glass was born in the Middle East. Glass artists together to take that sand and turn it into a glass wall.

that you could see through so that you can stand in front of it and look at each other.

through the sand that goes back and forth, back and

I don't know if there is an ideal world. One time, my husband and I were, Philip and I were talking about the way the extreme right and the extreme left see the world. And I said, the extreme right wants a world that never existed. And the extreme left wants a world that never can exist.

And then there's all the rest of us who are somewhere in the middle, the various middles, trying to be realistic about this world. I mean, we do have death and that's a basic part of life. And loss and grief. The ideal world to me would be that people actually deal with their grief and not project it onto others.

that people deal with their own fears without projecting it onto other people, without imagining that someone else is other to them.

Well, when I was four years old, 1945, and I remember this from the radio.

the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

this amazing technology that we had developed.

And it's how do we use the technology to bring us together and not destroy? I mean, was one of the most creative, destructive. Creating the bomb was the most creative, destructive.

act of mankind, harnessing that atom.

And we used it to destroy 100 ,000 people like that.

And yes, we have all of our justifications. People always have justifications.

We always have our justifications of why.

But it was a use of technology that created such profound fear in this world.

that still haunts us. And people are still creating these atomic supplies. mean, it's...

So for me, my mother lived to be 95 years old and I did a video with her because I wanted her great, great, great grandchildren to see her at some point.

I said to her mom, do you have any regrets in life? And she answered, my only regret, I was born, what, in 1911, and a war was beginning, and we're still having wars almost 100 years later.

And I said, in terms of your family though. And she said, no. And my mom dreamed of a rainbow family with every kind of, whoever people had to be. And we have almost every nationality in our family.

either through marriage or adoption. We have gay, we have straight, we have the whole mixture. I said, Mom, the world that you dreamed of was lived out within your family. How fortunate. And she had a very, very chaotic world that she came out of and then helped create. But in her old age, she could see that this dream of people.

of all kinds being able to work together, that that was lived out in her family.

Jiani (29:37)

We're moving toward that.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (29:38)

I hope so. I hope so.

many, I have quite a few grandchildren and they're mixtures of all kinds of things and it's wonderful to see. Two of them speak Chinese and English at the same, and I'm so glad. I'm just so pleased. And they're a mixture and they're explorers.

Jiani (29:56)

Beautiful.

Yeah.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (30:08)

is quite wondrous.

Jiani (30:10)

I really hope the global citizenship can be something real, can really happen. Because right now, it's still very tough. And we... I mean... We're not only... We're having war and we're tightening up all the immigration policies and process

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (30:22)

I...

Jiani (30:32)

I mean...

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (30:33)

You know, it's so interesting being in Lithuania and painting a mural. My grandfather left Lithuania in the 1890s and he left it, he was a Jew.

And it was in many ways very dangerous for Jew to be there. And he came to America. And I have thanked my grandparents, one who left Poland and others who left Belarus, but of course all that land was Russia at one point and this and Ukraine. And going there to Lithuania and painting a mural.

based on the heart of the storyteller, with a wonderful little figure named Froggy. Frog Dreaming is his whole name. And being able to thank my grandfather for the courage it took to go across an ocean not speaking a word of English.

and to give me the life that I have, the life they dream might be possible. It was a very powerful experience. And to work with these young Lithuanian art students doing this mural.

is very

complex and moving experience. And then to go to Lviv, Ukraine, which was Lviv, Poland during the war. I mean, that part of the world has suffered so horribly. And to be able to work with these young people and create the joy of these murals and celebrate with other people.

knowing the terrible things that had happened in these places over the last century, if not longer, was such a gift. And maybe that's, and you know, it's a drop in the bucket, but maybe that's, that's what we can do with art. I never imagined painting a mural in Lithuania. And then the magic happened.

Jiani (32:17)

Yeah, that's a surprise.

Yeah.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (32:20)

Right? You have the word magic behind you. The magic happened.

And it's process.

Jiani (32:24)

And it's the process

that you're creating. It's weaving and resonating with some original starting point and weaving back into this current moment.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (32:37)

Yes.

Exactly, I mean, my grandfather could never have imagined that that was possible when he left Lithuania. Never. And that the main part, the storyteller for me was my grandma Rosie, who would tell me wonderful stories. I'd sit by her bedside. She had a childhood diabetes, so she was in bed a lot.

And she'd tell me stories about the shtetl that she came from in Poland. And I knew everybody in that shtetl was murdered. And yet she'd tell me about so -and -so and we'd laugh. And they were all alive again. And she's in part the model for my storyteller, that her stories would keep this...

for this world alive in some ways, but not in a sentimental way, but in, with so much richness for a child to listen to. And then to go there and be able to let the storyteller tell a story about Froggy in visual images. What a gift.

And I think each of us has an opportunity to create the magic. I keep seeing the word behind you.

Jiani (33:51)

need to be open to

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (33:51)

I mean, you do it, you do it

in your podcast, you do it all the time.

Jiani (33:56)

Yeah, and we hear people's magic stories and I think I'm able to resonate and make connections and the dots is based on what you just said is our ability to let go and be open to possibilities because the world is much bigger than what we see here and once we release the control of this

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (34:22)

Yes.

Jiani (34:26)

and open our mind to the bigger possibilities. And that's where magic happens. That's where we, our perceptions got expanded and we feel released. We can feel joy without fear. We can feel abundance without fear.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (34:42)

Yes, without fear.

without fear, that's the operative word. so when you ask about the world that I imagine is for people deal with their own fears instead of projecting them onto other people, like onto immigrants. In this country, we're all immigrants. My husband being his father was Hopi Indian.

So they immigrated a few thousand years ago, maybe 10 ,000. His closest ancestral DNA are burials from the 800s. So he's been here a long time, his ancestors. Otherwise, we're all immigrants in this country.

And that's the power of this country. Why we're afraid of immigrants. It's like being afraid of ourselves for crying out loud.

Jiani (35:38)

yeah yeah that's that's yeah

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (35:42)

Let's pay attention to that. Immigrants built this country and not just immigrants, slaves also, people who were forced to come here.

They were not immigrants, even though Ben Carson called, used that term at some time, I couldn't believe it. No, they were brought here against their will. Immigrants aren't brought here against their will. Immigrants choose to leave a place and go to another because they have hope for something else.

Jiani (36:21)

and you'll be mentioning about the magic.

What did you... when you were maybe around 11 years old What did you enjoy doing that time disappeared for

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (36:36)

Reading. I love to read.

Jiani (36:37)

reading.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (36:39)

I love to be with my friends, my friend Gabby Flores and my friend Margie Haney. We're still friends since we were 10 years old. I love being with them.

I love to read. I love to disappear into stories that... I remember reading Thomas Wolfe, McComberd Angel. I just, I love to read. Because they were magical worlds.

Jiani (37:05)

I love that. I think of really,

yeah, stories are words weaving together to create world.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (37:13)

That's right.

That's what the word text actually comes from the word text array, which means to weave. So when you say stories are words woven together, yeah, the word text comes from the word to weave. And it's magical. Yeah.

Jiani (37:27)

Textile, yeah.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (37:30)

texere is to weave. And if you look at words on a page, they are woven. mean, to me, having been a tapestry weaver was like weaving language with yarns. And then images would emerge.

Jiani (37:45)

And music is weaving too.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (37:48)

Yes.

all around us.

Jiani (37:49)

What role does Childlike Wonder play in your life? What?

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (37:52)

What,

wait, there's a coyote outside. I just saw a coyote walking across, how wonderful, outside my studio. I was so surprised, you don't usually see them during the day. How beautiful to see them. I'm sorry, what did you say, Jiani?

Jiani (38:06)

Yeah

What role does Childlike Wonder play in your life?

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (38:16)

I think it's, yes, seeing that coyote was so incredible. That's the role. Childlike wonder, I think, is what allows the magic to happen. And when I start going too fast and when I start thinking about outcomes, it's not that I don't plan.

Jiani (38:16)

I think I just saw that.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (38:36)

But if I get too caught in that where it's more like trying to control something that I can't control, then that wonder disappears. I don't have access to it. I

I was thinking about a series I did in 1989 called Choco. There's a book that's going to be done about it. And one of the essays by a wonderful, wonderful writer, Dana Gaston, talks about how when I camped for a month by myself in the Southwestern desert, when I was trying to find myself again,

after years of, well, I'd lost myself. And how the light here was so magical to me. I was living in Northern California then. And it was a light that I knew as a child in Los Angeles. And I think what happened was the wonder returned.

and that child came alive again. And I'd lost touch with her. You we lose touch with those parts of ourselves. And luckily, I had enough sense and it was the right time. My kids were old enough that I could spend a month by myself just walking in the...

canyons in the southwest sleeping out under the stars. It was magical. And that child came alive. And so the rocks were alive. Everything becomes alive when you're with that child. Everything becomes alive.

Jiani (40:06)

There's some healing powers whenever we're able to connect with that child. And as you mentioned, for leaders, you would recommend them to keep some crayons, watercolors, pencils there. It's so true. Clay, it's just so true.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (40:12)

Yes.

play.

just a small

bag of clay that they keep moist. It's so simple.

Jiani (40:31)

Yeah, everyone, everyone who are doing

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (40:33)

everybody.

Jiani (40:43)

anything trying to reach a particular outcome on their journey on their adventure. The crayons, the clays, the water color pencils are protections for their heart and their inner magic which they have when they first came here.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (40:58)

Yes.

It can bring us back to ourselves. Just say, I need to stop now.

You can just even taking one crayon and just coloring with it for just five minutes. And I think something shifts here.

Best when we were so driven.

Jiani (41:19)

I was once lost touch with the Childlike

and

The moment that I was able to remember and reactivate and reawake, I was crying like there's no tomorrow. was like crying and crying and crying.

And the moment that you are connected, I did that through like meditation, watching really well made movies about a woman connecting with her inner child, a younger version of herself many, many times. And once that's been awakened, you have this like sense of lightness, like feels like

you are realigned into the essence of who you are. The... what's the word? The original settings where you was made and it's a big relief, release and relief and happiness and joy, contentment.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (42:15)

I'm sorry.

Jiani (42:26)

coming from that moment. So I can.

feel part of you where you went out in

forest at night and sleeping under the stars and hearing the sound of the evenings of bugs and animals and all that.

magical place.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (42:44)

It helps, it helps again, slow everything down. It allows room for reflection.

It's not always having to achieve.

It just allows room for other things to happen.

Jiani (42:55)

What do you think is your magic?

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (42:57)

What do I think?

Jiani (42:59)

is your magic.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (43:00)

Well, the coyote walking past as we were talking. I mean, it's actually, it's everything. I've been sitting here this morning with a burning tool, burning holes in a piece of Cozo paper that I put beeswax on probably 15 years ago.

and then turning them into little pieces, little burnt, let me see if I can hold one up, little tiny burnt pieces. And I'm gonna be using them on a large glass piece that I made. I don't know if it will work or not, and there'll be hundreds and hundreds of them.

But it's the process of how each one of these looks so different. They all come from the same piece of paper.

And they each look so different and I'm very curious to see what are they gonna look like when they're speaking to each other on this 48 inch by 24 inch piece. I mean, this is one inch. Again, it's a grid that I'm filling out.

So it's organized and yet I have no idea how it's gonna feel. One time I was working on a six by four foot painting with thousands of little glass shards I had made. And it spoke all the way until I put the last one on and it went dead. It just died. It said nothing.

It was very puzzled. We're talking about weeks of work.

And then I stood back and I looked at it and I realized, ⁓ right there, there's something intruding there that's not allowing my eye to wander.

And sure enough, just made a couple of tiny changes and it all came back to life again. So the magic is working with what we think of as inanimate and letting it live.

And it is magical, Jiani. It really is to be in this studio each day and to work.

and to know.

You know, life is very complex.

You know, we're born.

We live, we die.

and knowing that we die. In the red painting, the one I did in 1987, when I finally got to the source of what was going on in that painting, it was birth, death, sorrow.

And I think if we dealt with that.

with the sorrow that we carry, that there's a way that we get to have joy. And again, sorrow and fear, if we really worked with them. I had to go through a lot of therapy myself. I had to do a lot of therapy and healing of myself, both in my art, but hopefully then my art.

is universal in a way that it touches other people in that place in themselves. That's what I would hope

that it's been healing for me.

and can be healing for others. I'm not trying to make it healing. It's just where it's always come from.

Jiani (46:17)

it's being present and then the process follows

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (46:18)

Yes.

They go together.

You can't be in process if you are not present.

Jiani (46:26)

and thyme is a magical ingredient

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (46:28)

It's a very magical ingredient. It's really a, it exists and it doesn't exist at all. It's, and if we can think of it as those two things.

Jiani (46:37)

It makes everything meaningful.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (46:39)

Yes, each moment.

And you aren't looking for meaning. It's just, it's what it is. You know, when I was in Lithuania after we finished the mural in Ukraine in Lithuania, we had like four days in Vilnius where we got to sightsee. And the organizer, Ray Bartkis, a wonderful artist, took us to this village.

that had become a tourist trap since he'd been there. He found it disturbing. But we went to see this castle, a reconstruction of a medieval castle in the middle of a lake. And as I was walking to it, there was a man in a wheelchair on the side of the path and he had terrible, terrible spastic arthritic body.

And I realized I went, somehow it symbolizes so much of what that trip was about for me. I said to my friend Phil from the UK, who was one of the muralists, said, Phil, I need a minute here. And I went over and I took his hand. And I held his hand and we just looked at each other. And he smiled and, you know, he was moving with.

I don't know whether he had MS or what it was. And then we walked and we looked at the castle and we saw torture devices that had existed. And I learned what they had done in those devices. Sort of the worst of humanity. And then as we were walking back, there he was again.

I had a brother who got polio when he was five and had braces and crutches his whole life.

two brothers, but David was my younger brother. And he was a force of nature. And he actually, when he graduated law school at Berkeley, he became a lawyer for Cesar Chavez. And he was intense. But he had, with post polio syndrome in his 50s, he had to be in a wheelchair. And he told me, I hate being in a wheelchair. People look down on you when they speak.

Jiani (48:44)

Mm.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (48:44)

and they often don't even see you. And that's always stuck with me. And I went over to the man, and he saw me coming when I was coming back, and his smile was just incredible. And I went over, we held hands, I kissed his forehead.

And then we both went like this as we said goodbye.

And that was as magical a moment as any moment on the entire trip.

It just connected so many things for me.

And that's art to me.

in the deepest sense.

Jiani (49:18)

It's a connection.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (49:19)

Yeah, that deep, deep connection. No words. I mean, he couldn't speak. He was trying to speak, but all he could do is make sounds.

Jiani (49:28)

Yeah.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (49:28)

And

I didn't have to speak.

And if I carry, there's so many things that I, so many memories I carry from that three weeks in those two countries, but that's at the heart of it, at the absolute heart of it, was that connection without words. It was simply the moment.

Jiani (49:46)

Thank you for sharing.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (49:48)

It's been wonderful talking with you, Jiani.

Jiani (49:50)

It's so wonderful to be at the present moment hearing your stories.

and feels as if feels as if I'm with you like I'm just by your side and seeing what happened and feels like I lived your life for that brief moment

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (50:09)

that you have such empathy that you can enter that. Thank you.

Jiani (50:13)

powerful moment and

Sometimes it's hard for people

always be in that moment because of all the

things that we attach to ourselves and perceptions.

and all that.

and sometimes people may be hurting inside however they wanted to keep in that image

and feels like as if they could not afford to be a pure, loving and deeply connected being.

So I hope our conversation, the stories of Judy.

can really.

help us to remove all

mess and help us to really see us for who we are and everybody.

We have much more in common than differences.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (50:58)

Yes, yes, yes, we don't need to be divided.

Jiani (51:03)

So if you are inspired by Judy's story, please, please connect with her. Her information and contact information and social media accounts are all in the show note below. So we encourage you to get connected and create new stories weave new stories. That brings us closer together.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (51:24)

We've new stories.

Jiani (51:29)

thank you Judy

Judy Tuwaletstiwa (51:29)

Thank you, Jiani.

You have a wonderful vision.

Process Over Product

What makes Judy's approach revolutionary isn't technical mastery—it's her commitment to process over outcome. In the mid-1980s, she embarked on an extraordinary experiment: painting 100 different works on a single six-by-four-foot canvas, photographing each iteration before painting over it, knowing "none of the paintings on that canvas would ever exist except as memory."

The process taught her the most essential lesson of creative leadership: how to let go. "What I learned is how to let go in art." It didn't matter whether I loved or hated what I created. It was going to disappear.". She discovered that, when she loved a painting, she'd sit with it for three days before continuing. When she hated a painting, she would also sit with it for three days before appreciating it. Then she could let it go.

Time became a magical ingredient. Her White Continuing Painting took six months, the Black Continuing Painting two months, and the Red Continuing Painting just two weeks—yet all yielded roughly the same number of photographs. "We're always in such a rush," she observes, but real creative work requires patience with natural rhythms.

Art as Universal Language

Judy's philosophy extends far beyond the studio. Quoting philosopher Immanuel Kant, she reminds us that our hands are "the visible part of our brain." Working with clay reveals something profound: "Our hands are equal in dexterity. We don't have a second thought about doing the finest work with our less dominant hand."

This insight transforms how we think about decision-making and problem-solving. Clay, formed over "millions of years," connects us to geological time when we're trapped in artificial urgency.

Practical Tools for Leaders

Her prescription for leaders is elegantly simple: "I wish every leader would have a big box of crayons, with 48 colors, in their desk drawer.." Add watercolors, clay in a plastic bag—nothing fancy, just materials that reconnect us with tactile thinking.

When she taught teachers, she would say, "If students had a small plastic bag of clay and they started each morning working with the clay letting the clay change like the Continuing Paintings, you would have a much calmer child for the rest of the day," The same applies to corporate environments: twenty minutes with materials transforms entire workdays.

The problem with constant rushing, she explains, is that it feels like "an escalator going down and you're running up it—and it's exhausting. I'm one of those energizer bunnies, but the slower I go, the more threads weave themselves together. The more I'm able to see that."

Global Leadership and Connection

Recently, painting murals in Ukraine and Lithuania, Judy witnessed art's healing power firsthand. Ukraine now has "probably more art therapy programs than any country, both for the soldiers and for the children." Art becomes medicine in a wounded world."

Her vision extends to seemingly impossible conflicts. She used to picture the sand that blows back and forth between Israel and Gaza, sand that did not know boundaries. She dreamed of Palestinian and Israeli glass artists collaborating: taking that shared sand and creating "a clear glass wall that would encourage people to stand and look at each other.

This isn't naive optimism but practical wisdom from someone who understands that "art really can connect what is divided." Her family embodies this possibility—her mother's dream of a "rainbow family" realized through marriages and adoptions across all nationalities, orientations, and identities.

The path forward requires confronting our deepest fears. She says, "The ideal world would be one in which people deal with their grief and fear rather than projecting it onto others."

At 83, having painted murals in her grandfather's homeland of Lithuania—the same country he fled as a Jewish immigrant in the 1890s—Judy embodies the transformative power of creative courage. Her hands-to-heart gesture isn't just an introduction; it's an invitation to remember that we all carry the capacity for connection, healing, and hope.

The magic happens when we slow down enough to let it.

⭐ Our Guest

Judy Tuwaletstiwa

Judy Tuwaletstiwa creates visual narratives about fragility, strength, and resilience using materials from kiln-fired glass to organic matter like feathers, ash, and sand—each artwork becoming a conversation between color, texture, and form that evokes intuitive narratives of embodied knowledge. Recipient of the 2023 New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts, her work emanates what critics describe as a palpable healing force, with publications including The Canyon Poem, Mapping Water, and the forthcoming Chaco (2025). Her art lives in private, public, and museum collections worldwide, including special editions housed in Yale's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library and the Corning Museum of Glass' Rakow Library.

Judy's Magic

Judy's magic lies in her ability to make the inanimate come alive—working with thousands of tiny glass shards or burning holes in beeswax paper, she transforms ordinary materials into vessels of profound connection. "It is magical, Jiani. It really is to be in this studio each day and to work... and to know that we die," she reflects, finding joy not despite life's fragility but because of it. Her deepest magic moment came not in her studio but holding hands wordlessly with a man in a wheelchair in Lithuania, demonstrating that art's highest purpose is creating "that deep, deep connection" without need for words.

The magic happens when we slow down enough to let it.

Credits & Revisions:

Guest Alignment Reviewer: Judy Tuwaletstiwa

Story Writer/Editor: Dr. Jiani Wu

AI Partner: Perplexity, Claude

Initial Publication: Aug 1 2025

Disclaimer:

AI technologies are harnessed to create initial content derived from genuine conversations. Human re-creation & review are used to ensure accuracy, relevance & quality.